In summary, a condenser, also known as a distiller, is used to change the phase of fluids from a vapor (gas) state to a liquid state by cooling them (removing the heat from the hot gaseous fluid) in various industries. The main function of a condenser is to remove heat from a high-temperature gaseous fluid using another cooling medium such as air, water, or any other cooling fluid. For example, in a household refrigerator, the condenser works by cooling the refrigerant gas (freon) flowing through the coils at the back of the refrigerator, causing it to change from vapor to liquid. Similarly, in the chemical industry, it is used as a distiller, among other applications.

Condensers come in various designs (including air-cooled, shell and tube, plate, etc.) and sizes, but their fundamental function remains the same.

### How Does a Condenser Work?

Here, we explain the operation of shell and tube condensers and air-cooled condensers, which are among the most commonly used types.

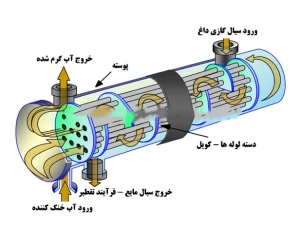

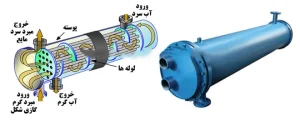

**Operation of a Shell and Tube Condenser (Shell and Tube Type)**

In this type, a series of small-diameter tubes (coils) are placed inside a larger-diameter shell. Typically, a low-temperature cooling fluid such as water flows through the small tubes, while a high-temperature gaseous fluid flows around the tubes inside the shell. Heat exchange occurs through the walls of the small tubes, where the cooling fluid absorbs heat from the hot gas, gradually converting it into a liquid. The liquid collects at the bottom of the shell and is discharged through a drain at the bottom of the condenser.

Since water is used as the cooling medium in this model, it is also known as a water-cooled condenser. The water, having absorbed the heat from the hot gas, must be cooled before it can return to the circuit to again absorb heat from the hot gaseous fluid. Therefore, the warmed water is pumped to a cooling tower, where it is cooled down before being returned to the condenser.

Structure, Operation, and Function of Air-Cooled Condensers

**Operation of the Shell and Tube Condenser**

In a shell and tube condenser, the space inside the shell is usually maintained at a relative vacuum. This vacuum is created due to the difference in specific volume between the vapor and the condensed liquid. Sometimes, however, the situation is reversed, and the cooling liquid (such as water) flows through the shell while the hot gaseous fluid flows through the tubes.

This type is widely used in devices such as water-cooled compression chillers and various industrial processes.

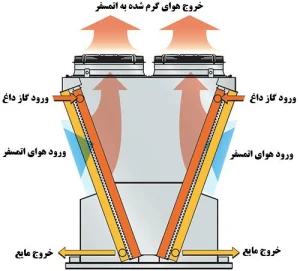

**Structure, Operation, and Function of Air-Cooled Condensers**

When there is limited access to water, when water cooling is not feasible due to hygiene reasons, or when only a small amount of condensation capacity is needed, an air-cooled condenser is used instead of the shell and tube (or water-cooled) type. As shown in the diagram below, this air-cooled condenser, also known as an air-cooled unit, operates similarly to a radiator. In this type, the hot gaseous fluid enters the condenser’s tubes (coils) from one side. One or more fans then blow air over the tubes, removing heat from the fluid, which gradually cools the gas until it condenses into a liquid at the tube’s outlet.

Because this model includes fans, it is also referred to as a fan-cooled condenser.

This type is also widely used in air-cooled compression chillers and various industrial processes.

Air-cooled condensers are easily cleaned of surface contaminants, and to maintain their efficiency, it is essential to keep the coils and fins clean.

These two models are among the most commonly used condensors in the industry.

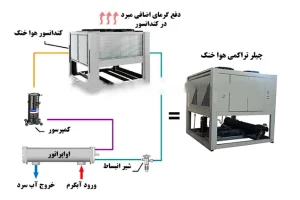

In general, there are two types of compression chillers: air-cooled compression chillers and water-cooled compression chillers, which will be discussed in this text. The water-cooled chiller is also known as a chiller with a cooling tower, and its structure will be mentioned here as well. Water-cooled and air-cooled compression chillers are the most commonly used types of chillers in the industry, with minor differences between them, which we will explore.

The components of air-cooled and water-cooled compression chillers are very similar. Both types feature a compressor that compresses the refrigerant in the circuit, an expansion valve that expands the refrigerant in the circuit, an evaporator that acts as a shell-and-tube heat exchanger where water is cooled by the refrigerant, and a condenser heat exchanger. The main difference between them lies in the type of condenser used.

**Air-Cooled Chiller**

In an air-cooled chiller (or air-cooled compression chiller), where the condenser is shown with a yellow-bordered box in the figure below, there are several air-cooled condenser heat exchangers (similar to radiators) arranged in a V shape facing each other, through which the refrigerant flows via complex coils. Fans located above the condenser blow air through the air-cooled condenser, absorbing the excess heat from the refrigerant and transferring it to the atmosphere. Air-cooled compression chillers are usually installed in open spaces such as rooftops or courtyards, while water-cooled compression chillers are typically installed in mechanical rooms and connected to a cooling tower located in an open space via piping.

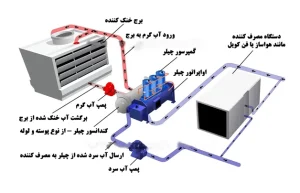

**Water-Cooled Chiller**

In a water-cooled compression chiller (also known as a water-cooled chiller), where the condenser is shown with a yellow-bordered box in the figure below, the condenser heat exchanger is of the shell-and-tube type. In this system, the refrigerant flows through the tubes, and heat exchange occurs with water flowing around the tubes (inside the shell), allowing the water to absorb the excess heat from the refrigerant. The now-warmed water itself needs to be cooled. Therefore, the warmed water is pumped to a cooling tower (or cooling tower) where it is cooled and then returned to the condenser. This is why this system is also referred to as a chiller with a cooling tower. Thus, a water-cooled chiller requires a cooling tower, whereas an air-cooled chiller does not need one.

**Part of the water sent to the cooling tower (cooling tower) by the pump evaporates in the tower, and fresh water must replace it. Therefore, the chiller with a cooling tower, or water-cooled chiller, consumes water, whereas the air-cooled chiller does not consume water. From a maintenance perspective, the water in the cooling tower is prone to microorganism, bacteria, and other growths, requiring chemical additives to prevent these issues and periodic water changes. Naturally, such concerns are absent in an air-cooled chiller, where maintenance is limited to cleaning the surface of the condenser tubes and fins. In terms of cost, the air-cooled chiller is somewhat more expensive than the chiller with a cooling tower because the production cost of an air-cooled condenser is higher compared to the water-cooled shell-and-tube condenser and its cooling tower.**

**Types of Chiller Condensers**

All compression chillers are equipped with two heat exchangers known as the chiller condenser and the chiller evaporator. Together with the compressor, expansion valve, and refrigerant flow, these components create a continuous cycle of cooling water or air. Condensers and evaporators are also used in other cooling and heating systems such as ductless splits, VRF systems, and more.

Chiller condensers come in two completely different types. As mentioned, a condenser is a type of heat exchanger where heat transfer occurs between the refrigerant and either water or air. If the refrigerant transfers heat to water, it is referred to as a water-cooled chiller condenser (water-cooled condenser). If the refrigerant transfers heat to air, it is known as an air-cooled chiller condenser (air-cooled condenser). Both types are illustrated in the figure below (highlighted with yellow boxes).

**Water-Cooled Chiller Condenser**

A water-cooled chiller condenser is typically a shell-and-tube type heat exchanger (in some applications, a plate type may also be used). In this design, the refrigerant flows inside tubes (usually made of copper), while water flows around the outside of the tubes. The heat from the refrigerant is transferred through the tube walls to the water. This heated water then needs to be cooled down before it can return to the condenser to absorb more heat from the refrigerant. Therefore, an additional device called a cooling tower is installed alongside the water-cooled chiller to cool down the hot water exiting the condenser. By transferring its excess heat to the water, the refrigerant changes phase from a gas to a liquid.

Details of the Structure of a Water-Cooled Condenser (Shell and Tube):

**Air-Cooled Chiller Condenser**

The air-cooled condenser of a chiller, which is larger in size, is a type of air-cooled heat exchanger. In this system, the refrigerant flows through tubes, and air is blown around the tubes (by fans). Heat is transferred from the walls of the tubes to the air. Since the refrigerant directly dissipates its excess heat to the air, there is no need for a cooling tower or water in an air-cooled chiller. The refrigerant changes phase from gas to liquid by releasing its excess heat to the air.

Details of Air-Cooled Condenser Structure:

**Chiller Evaporator**

The evaporator in a chiller system is often a shell-and-tube heat exchanger. Unlike the condenser, which transfers heat from the refrigerant to water or air (causing the refrigerant to change from a gas to a liquid), the evaporator allows the refrigerant flowing through its tubes to absorb heat from the surrounding water. As a result, the temperature of the water around the tubes decreases, potentially lowering the water temperature to near or below freezing. This chilled water is then pumped for cooling applications to devices such as air handling units (AHUs) and fan coils, or to industrial equipment for cooling purposes.

The evaporator can also be an air-cooled heat exchanger. In this setup, the air-cooled evaporator is integrated within the air handling unit. The refrigerant in the evaporator tubes absorbs heat from the air blown by the fan across the tubes, directly cooling the incoming air to the building. This type of setup, where the chiller’s evaporator is embedded within the air handling unit, is referred to as a DX (Direct Expansion) connection. The advantage of this arrangement is that instead of cooling water and pumping it to the air handling unit, the refrigerant directly cools the warm air in the air handling unit, thereby reducing energy loss.

*Author: Engineer Amirali Ghiasvand*